And Barcelona was filled with "Nuvolaris"

The pilot Tazio Nuvolari, cover of the first issue of the magazine “Pirelli. Rivista d'informazione e di tecnica”, 1948 (Pirelli Foundation), www.rivistapirelli.com

Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari (1892-1953) deserves to appear in every list of the best drivers in history. He was a hero during a time when competing posed a serious risk to life, his career combines courage and tenacity in equal parts. Linked to racing as a way of life and personal refuge, we could say that Tazio raced to live, more than lived to race.

He began late by current standards, but was successful. Since his debut in 1920 at 28 years old, Nuvolari did not take long to reap success on two and four wheels in his native Italy. His leap to international competition was just a question of time. On the brink of autumn 1923, he turned 31. Since 1921 Penya Rhin, a Catalan group of motor enthusiasts, organised a competition in the Vilafranca circuit, a route tracing Barcelona which connected 14 km of dusty roads surrounded by vineyards. Just before the third edition of the race, the organisation received the affirmative answer from only one Italian manufacturer, Chiribiri, who would provide two 1,500 cc Tipo Monza “voiturettes” for Amedeo Chiribiri and Maurizio Ramassotto. However, the exclusion of the latter, combined with “Deo” Chiribiri and Tazio Nuvolari's friendship, presented the possibility of an international debut. He would do it with a triple challenge: Vilafranca race and the inauguration of the new National Terramar Race track.

Tazio set sail aboard the steamer “Guadalquivir” heading to Barcelona on October 11, 1923. He arrived with the novice label, in the face of the potent Talbot armada, led by the Frenchman Albert Divo. The latter would win on the 21st of the same month in Vilafranca, when Nuvolari, affected by mechanical problems, finished fifth following an epic recovery. The motorcycle did not accompany him either a week later in the Terramar race, which he attended on the handlebars of a Borgo. Nuvolari was destined to leave a mark, as was demonstrated in the voiturettes race which closed the opening week of the circuit. Dominated by the Talbots, led by Dario Resta, Nuvolari crossed the finish line in fourth place after a frenetic recovery. An extract from “Mundo Deportivo” newspaper from November 5, 1923 reported this: “Nuvolari was the only one who, for most of the race, with great courage and virtuosity, unleashed a thrilling duel against opponents who were fastest, but not as audacious as the Italian who received the warmest ovation yesterday.” Nuvolari had left a mark.

A decade later, Penya Rhin recovered its “Grand Prizes” in Montjuïc, a challenge carried out with less resources, than will and organisational insight. The Penya authorities saw the perfect claim in Nuvolari, in what was supposed to be the fourth historical race, set for June 25, 1933, for which they disposed of a month and little (or no) financial help from the administration, according to Javier del Arco's book “40 años del automovilismo en el circuito de Montjuïc”, so they travelled to the GP in Nimes to persuade him. The Italian, who that same month would win the Le Mans 24 Hours, gave them his word, backed by the “good memories” of his international debut and the warmth of fans in Vilafranca and Terramar.

This was the start of a triennial love and hate between Nuvolari and Montjuïc. The magic mountain circuit, famous for hosting four F1 GP between 1969 and 1975, saw him suffer due to mechanical problems in 1933, affected by physical consequences of a previous accident he had to quit in 1934, and made it to third on the podium behind the wheel of an Alfa Romeo P3 in 1935, losing to the unreachable Mercedes-Benz W25B.

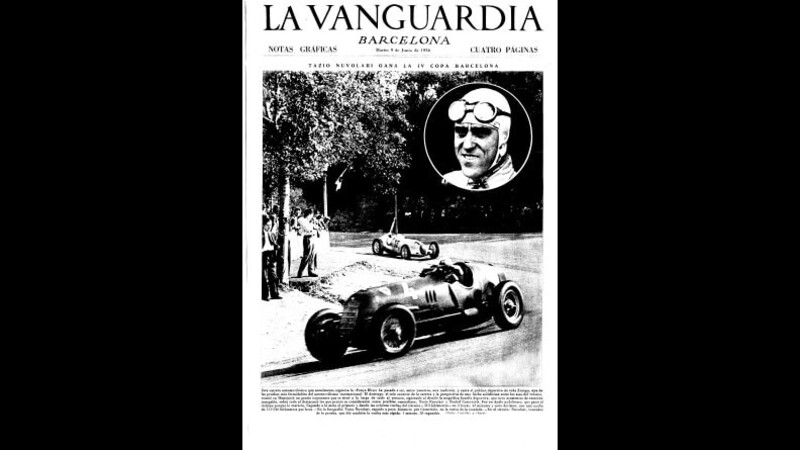

That was until 1936 arrived. Nuvolari registered for the 7th Penya Rhin GP behind the wheel of a Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo 12C, an inferior technical assemblage compared to the German colossus, Caracciola and Louis Chiron's Mercedes W25, and the Auto Union driven by Ernst Von Delius and Bernd Rosemeyer. But that June 7, the Italian achieved an epic feat underpinned by his courage and tactic intelligence.

The race, which began with a grid defined by a draw, became a head to head contest between Tazio Nuvolari and Rudolf Caracciola. The Mantuan did not take long to take the lead after surpassing both Mercedes –first Chiron and then Caracciola–, escaping with a devilish rhythm. The attending public (sources speak of a range from 50.000 to 100.000 people) witnessed the red Alfa's repeated fast laps with a roar, which ended up setting the track's record in 1:58, four seconds faster than the previous record which would remain intact for 28 years. Impressive. The duel in the boxes caused an ephemeral change in leadership, which Nuvolari recovered after a new refuelling by the thirsty W25 driven by Caracciola between the 52 and 53 laps. His lead: 26 seconds.

An epic competition phase started here. Logic indicated that Nuvolari would have to stop at least once more. This is what the Mercedes team thought, backed by the Italian ace's gestures who, lap after lap, motioned his mechanics to prepare a hypothetical pit stop. Caracciola swallowed the bait for many laps... until he saw it was too late and not even a furious final reaction was enough to surpass the Scuderia Ferrari. Nuvolari, who saw the squared flag with a little more than two seconds advantage (the timing system of that time cannot agree about this) had spared the last visit to his mechanics due to a flawless management of his Pirelli Stella Bianca tyres and an extremely efficient driving (he reached the finish line with 5 litres of fuel in the tank).

Nuvolari sealed a historic victory... as well as his particular reconciliation with Barcelona. Javier del Arco captured Nuvolari's statements at the end of his career in his writings about Montjuïc: “I am taking the best memories of this GP with me. I had a fervent desire to get even before this audience, which saw my debut as a race car driver, after performances of years past where luck was not on my side. I believe now I have left a good memory.”

Nuvolari would never race again in Barcelona, but his legacy marked the city for decades. His bold (and sometimes fearless) driving drifted into memory... and even into language. Since then, ‘to be a Nuvolari' means to drive a car at high speed. This is how, at a distance, and for almost half a century, Barcelona was filled with ‘Nuvolaris'.